I.A.

Somexki Collection

1 photograph

found in Armenia

Séroux

1 painting

Somexki Collection

1 photograph

Ghabor Collection

3 photographs

Alex Svi

1 question

Arles 2016

Collection Somexki

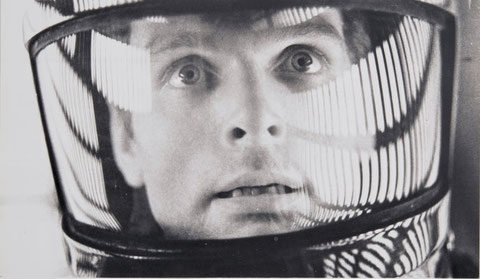

Photograph of a cinema shop window found in Paris taken from the science-fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey, produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick in 1968. The screenplay was written by Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Its plot was inspired by several short stories chosen by Clarke, mainly ‘The Sentinel’ (1951) and ‘Meeting at Dawn’ (1953). The film stars Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester and Douglas Rain. It follows a journey of astronauts, scientists and the sentient supercomputer HAL 9000 to Jupiter to investigate an alien monolith.

The subject of the painting is a reference to the artificial intelligence in Stanley Kubrick's film 2001. When Dave returns from an outing on Discovery One, HAL refuses him entry to the ship. Dave is now on his own. He goes off duty and disobeys.

He managed to open an emergency hatch from his vehicle and broke into HAL's storage units, disconnecting the holographic memory blocks containing the higher software layers emulating HAL's intelligence, leaving only the purely automatic functions essential to the ship.

Gradually regressing, HAL said to Dave ‘I'm scared’.

If intelligence and stupidity exist naturally, and if we say that AI exists, is there then something that could be called ‘artificial stupidity’?

Dr. Jay Liebowitz - Harrisburg University of Science and Technology

TO GO FURTHER

A closed door for infinity

A genre scene, a crime scene, a domestic scene - putting yourself on stage, making a scene, staging a scene like a painting in the theatre, is always a way of inhabiting a possible world in order to approach impossible truths.

The paintings we are talking about here show that we all inhabit life as actors, consciously or unconsciously, attentively or inadvertently. Nothing in us escapes movement. The whole earth dances to the beat, transforming our destiny into a hesitant waltz. Our actions have taken over everything. But it's becoming clear that we rarely, if ever, manage to grasp reality as a whole. Its complexity eludes us.

Slavoj Zizek puts it very well:

The real is simultaneously the thing to which it is impossible to have direct access and the obstacle that prevents this direct access, the thing that escapes our grasp and the distorting screen because of which we miss the thing.

We live in the image of the characters in these paintings, in an in camera setting that we don't usually understand much about. The field of art thus becomes exactly the opposite of that of social life, where over time there hovers the nagging scent of all the abandonments of position between what happens there and what doesn't happen there, more or less. In the end, for many people, an ideal is nothing more than a poor matter of circumstance. Sooner or later, everyone becomes a witness to this world championship of loss, mourning and nostalgia, which even has a radio station in Belgium.

But the great talent of pictorial space here is that it is the absolute antidote to a time that destroys dreams, sapping momentum and making ruins. The artistic space unfolded by the painting is that of the gaze around this question:

How do we inhabit our uncertainties?

It is also a space for anthropologists and ethologists to explore relationships outside the commonplace. You feel at home and elsewhere at the same time, outside the game of routines. The artists take us out of the ritornello, the routine of the interests of profiteers of good adventures, good opportunities... Artists and viewers, each contributes to the construction of a shared space, a milieu. The one cannot exist without the other. What you experience is life as a philosopher, in other words the intense pleasure of being able to rethink things from whatever starting point you choose. Philosophical curiosity catches us on the fly.

If, as William James said, ‘ideas are not what we think, but what makes us think’, the space opened up here is not what we look at, but what makes us look. It's the infinite that opens up, with the only limit being the creativity of a group that's complicit, tuned in and unrestrained.